Before the outbreak of the First World War, Dolly Shepherd was flying high – literally. She was a balloonist and parachutist with a display team for more than a decade.

It was a risky business but Dolly liked to push the boundaries and had earned a reputation as a daredevil who would go as high as she could in a balloon before parachuting back down to earth.

‘I used to like to go high because I had it in my head in those days that if I had to be killed I’d like to be killed completely, you know, good and proper. But the people used to like, if it was a clear day, they used to love to see you going high. It gave them pleasure. It gave me pleasure too.’

She retired from parachuting in 1913 - but when the First World War began the following year, she found a new role for herself.

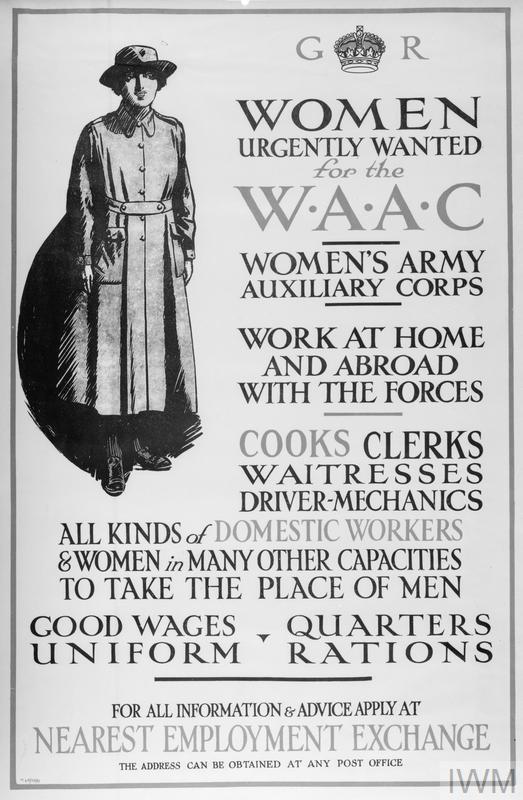

On 8 August 1914, Dolly signed up for the Women's Emergency Corps after seeing an advert in the paper. ‘All the men rushed to volunteer and so I thought I’d do what I could.'

Dolly and her colleagues in the Corps were told they were going to have to work hard and purchase their own khaki uniforms. They would practice marching in central London and didn’t always get the most positive reactions.

‘Of course people were all giggling and laughing and saying ‘Women soldiers! Just imagine having women soldiers. Whoever thought of such a thing’. And they used to sneer at us and all kinds of things.’

While some may have sneered, the women of the WEC were busy performing a range of duties for the war effort, from converting the Bethnal Green Workhouse into a hospital to treat soldiers who had been gassed to driving patients arriving at Charing Cross.

She also helped run a mobile canteen at Woolwich Arsenal. A horse and van had been provided by Harrods and the WEC would serve up tea and buns to the munitions workers– ‘always buns’, Dolly remembered.

Dolly and her ‘squad’ were prepared to deal with all kinds of emergencies – from providing first aid to accompanying fire engines when they were called out during Zeppelin raids.

‘You had to use your brains and do something. If you were to fall out of that chair and break something I’d have to do whatever I could and do it quickly.’

Dolly had learned to drive before the war and ended up driving supplies for munitions factories. On one memorable occasion, she was assigned to drive items from the Mint to the docks.

It was only when her cargo was unloaded that she was told that the white blocks she had been transporting – which she had assumed were munitions supplies – were in fact gold ingots that had been painted white.

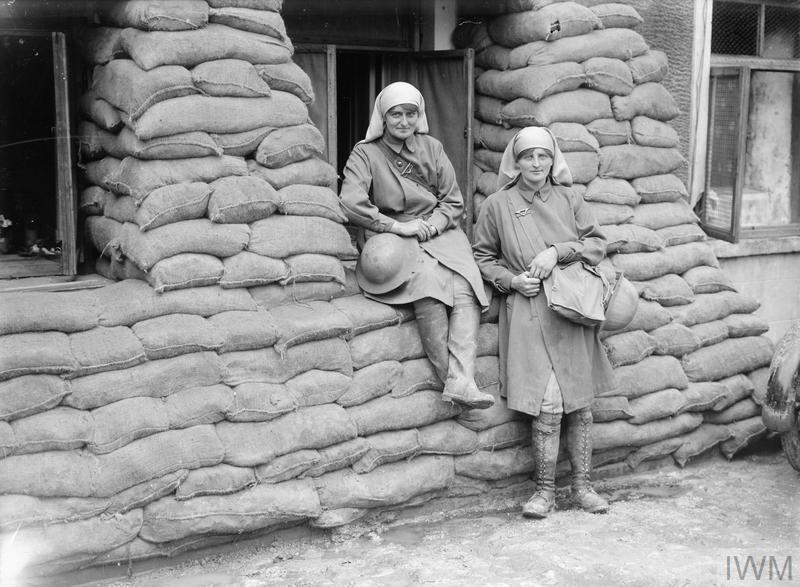

In 1917, she went to France where she served as a driver mechanic with the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps at Queen Mary's Camp in Calais.

One day, she found a General’s car and its chauffeur by the roadside. The chauffeur had been unable to fix an unknown problem with the car and had called for help – Dolly offered to take a look, although the driver was sure she would not be able to solve the problem.

‘At that time we wore long hair and we had invisible hairpins you know. So of course I got out one of my hairpins and start fiddling about and to this day I don’t know what I did. I suppose a bit of sand or something must have been in one of the jets of the carburettor or something like that. I don’t know really. Anyhow, I wound it up and it went.’

‘That same night there was a cup of milk left for me. So then we were really on, really getting to know each other….We were all in. We were a very, very friendly garage’.

Some people were a little harder to win over - one officer she was assigned to didn’t want to have a woman driver, told her his dog did not care for women and went as far as giving her step-by-step directions when they travelled. But when it was time for his regular male driver to take over again, the officer said he’d ‘rather keep the girl driver’.

Dolly’s job could sometimes be upsetting. Although she didn’t serve directly on the front lines of the war, she would drive officers very close to them.

On one occasion, she drove an Army Ordnance officer to repair a gun and when she got there, she could see grey uniforms of the Germans in the distance.

‘And our men – they were youngsters, they were C3s – they were running away. And this man had to arrest them. I was crying my eyes out then because you see then if you got a man running away or deserting they were shot. And so I drove home crying my eyes out; all the tears running down. And the men said ‘Don’t worry Miss. Don’t worry Miss. We deserve it’.’

Conditions were basic – there was no running water or heating in the Nissan hut where she lived with 8 other driver mechanics – and the hours were very long.

‘For the first eight months we were there we didn’t have one hour off,’ Dolly remembered. ‘And we had an air raid pretty well every night there and we were pretty well worn out.’

One night, Dolly and some of her colleagues got their hands on a bottle of Benedictine and set to drinking it.

‘You can imagine the state! Well there came the usual air raid and I went out and sat on a little white stone in the compound and every time they came to get me, so another shell would come down so they really left me. They gave me up as a bad job.’

Dolly and her friends woke up in the sick bay and were sent in front of a court martial because they were ‘unfit to perform duty when called upon’. When the colonel in charge asked them what they had to say for themselves, they had their answer.

‘We all said the same thing. If it happened tomorrow we should do exactly the same things we did yesterday because we’re tired out. He said ‘Well, what days do you have off?’ Have off! I said ‘we haven’t had a day off’.’

The result of the court martial was that Dolly and her friends were given a half day off per week.

In their limited free time, ‘mixing’ with officers was not encouraged.

But the officers found a way round the rules by hiring private rooms in hotels – the female driver mechanics would enter the hotels discreetly through the back door and enjoy a meal without getting in trouble.

‘So I mean you see we used to get fed, but it was really rather embarrassing because a private room in France means that you’ve got a bed in the room which we used to promptly smother with our overcoats and hats to disguise it as a bed. But they were very decent. All the officers were very good, they never took any advantage. Oh no, they were very nice. We worked hard, but we played hard.’

She was assigned to drive King Albert of Belgium to Bruges one day – when she picked him up in Les Baraques, he was sitting by a plane eating bread, cheese and pickled onions. Keen to know if he was as tall as he was reported to be, she pretended she couldn’t wind the car up to start it.

‘And so he said “Oh let me do it”. And he stood up and I stood up the side of him; he was about that much taller than me,’ she remembered.

‘But when we got to Bruges, oh, the excitement! People were giving me lots of banknotes and things and shaking me by the hand as if I was a heroine. But of course I’d brought him back you see. Oh yes, yes, that was an exciting time.’

In November 1918, Dolly remembers there was a feeling in the air that the end of the war was coming and ‘it might be any day soon'.

In fact, she recalled that three days before the Armistice, a rumour that the war was over spread around her camp in Calais.

'We went out of camp and we went down to the officers' mess when they carried me and her on their shoulders going round, you know, making merry and making whoopee.'

Although that turned out to be a ‘false armistice’, on November 11 1918, the war officially ended.

'It was so strange to have silence'

Dolly Shepherd: "Well, do you know, strangely enough we wept because the silence was so awful. You see we’d been used to the noise of guns all day long, all day long, all day long, it was so strange to have silence."

Audio clip: © IWM / Dolly Shepherd / Sedgewick

‘Strangely enough we wept because the silence was so awful. You see we’d been used to the noise of guns all day long, all day long, all day long, and it was remarkable how – of course we were pleased naturally – but it was so strange to have silence.’

She went home to England on leave in 1919 where she married a Captain Sedgewick, who had already been demobbed. But she was soon headed back to France, leaving him and the ring he had given her behind.

Usually, married women were sent home but Dolly wanted to stay and drive President Poincaré, the President of France, in a procession at Blanc-Nez. But her husband had other plans.

‘My husband got fed up with waiting, he went to the War Office and told them that we were married….And it came through…You’re to go home tomorrow. I left quite a lot of souvenirs behind and everything I didn’t have time for. I just had to pack the things because it was an army order. I had to come home. I was so cross because you see … I was looking forward to that procession. I thought it would have been rather nice as an end-up, you know wind-up to the war.’

Dolly’s memories of the war were recorded by IWM in 1975. She died in 1983.