IWM holds an insightful collection of oral history recordings of those who served in the Korean War, which was fought from 25 June 1950 to 27 July 1953.

After the end of the Second World War, Korea was split into two zones. The country had been occupied by Japan since 1910, and the victorious Allied powers agreed at The Potsdam Conference that Korea should be divided along a circle of latitude - the 38th Parallel.

Discover unique stories from those who fought in the conflict, which has become known as the 'Forgotten War'. While the war in Korea is thought to be overshadowed by the Second World War and the Vietnam War, the conflict was one of the bloodiest of the 20th century and led to the deaths of three million and thousands of casualties.

Hear from those who fought to defend South Korea during the three-year conflict and share their experiences of the 'Forgotten War' below.

Arrival: 1950

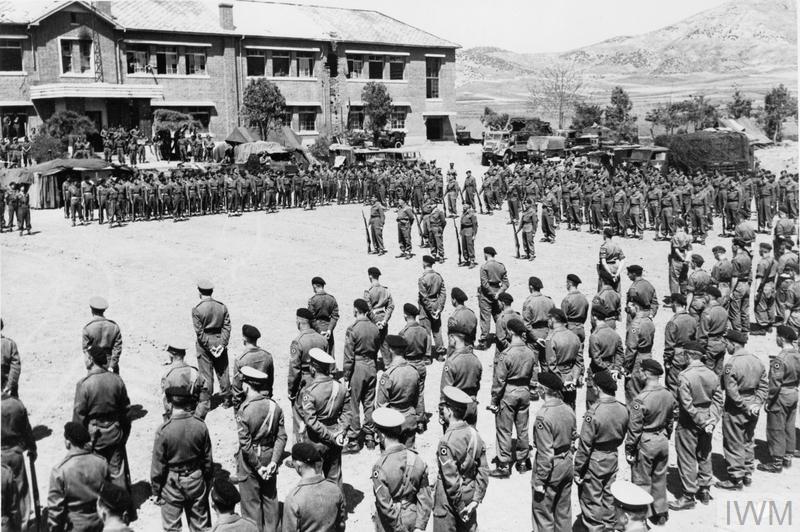

In August 1950, troops of the 27th Infantry Brigade began to arrive in Korea as the first element of the British Government’s contribution to the United Nations’ campaign to stem the North Korean invasion of the south.

The brigade was moved rapidly from Hong Kong to take up positions on the River Naktong in the Pusan Pocket.

When Captain John Shipster of the 1st Bn Middlesex Regt arrived at an airfield near Pusan, he soon found that some of the non-essential kit he’d brought would have to be ditched – literally.

‘I just threw them in a ditch and I never saw them again’

“I remember asking my Colonel, Colonel Andrew Man, whether or not we would be possibly going into action fairly soon, or going to merely show the flag in Japan for propaganda purposes i.e., that British troops are on the way etc.

And I remember asking him if it would be an order for me to take my golf clubs and my tennis racket. And he said, ‘by all means, John, take your golf clubs and tennis racket’. And I departed from the airfield, armed with my golf clubs and my tennis racket. It all sounds slightly blimpish, doesn’t it?

I got out of the plane on arrival, much to my amazement found the airfield was under shell fire. I was then carrying my golf clubs and tennis racket and I remember a large black Sergeant came along and said, ‘we’ve got a right lot of Charlies here’, or words to that effect. I wasn’t ashamed but I just threw them in a ditch and I never saw them again.”

Attack: September 1950

On September 21st, lead elements of the 27th Infantry Brigade crossed the Naktong River to attack two strategically important hills, in order to aid the breakout of the US Eighth Army from the Pusan Pocket.

After a fierce fight, the Middlesex Regiment captured what became known as ‘Middlesex Hill’ on September 22nd, whilst the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders moved up to attack North Korean forces on Hill 282.

On the morning of the 23rd September, two companies of the Argylls advanced up towards the crest of the hill and after a short but brutal fire fight succeeded in taking the position.

Corporal Richard Peet, speaking in the clip above, was there that day and recalled his friend Lance Corporal Joseph Fairhurst being wounded.

But Corporal Peet soon had to leave his friend to continue the fight.

Immediately they faced a counterattack from the North Korean held Hill 388 to the southwest. Under mortar and artillery fire, the beleaguered companies requested an air strike on Hill 388 and three American F-51 Mustang aircraft began to circle overhead.

Unfortunately the aircraft attacked the wrong hill, dropping napalm canisters onto the Argylls’ positions and forcing the defenders to abandon the crest.

Realising the seriousness of the situation, Major Kenneth Muir reassembled a party of survivors to return to the top of Hill 282 before the North Korean forces could acquire a foothold. In the ensuing fight Muir was mortally wounded by gunfire and the remaining small group of defenders, running low on ammunition, were forced to abandon the hill.

For his actions in organising the defence of Hill 282, Kenneth Muir was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross. The Argylls had 13 men killed and over 70 wounded, most being victims of the mistaken air attack.

‘It just decimated them’

“We lined up on the 23rd of September, it was, I’ll never forget that day. We decided to attack this hill. So we got in an extended line and we started climbing 282. I think we got about halfway up and we came under fire from small arms fire from some trees.

The first section went in and cleared the trees. And we started climbing again, we got a bit farther and then we came under small arms fire again, which was almost like another section of these North Korean troops.

I assume they were in section strength where they'd be sent to get their forward slopes.

We got going again and then suddenly, we came under pretty heavy fire. Joe first got wounded, he got shot in the tummy, and I put him against a tree and put a cigarette in his mouth and left him for the first aid people to pick him up.

We just went a bit further on and the Platoon Commander went down, he was shot in his feet. And by this time it was constant fire, and then it stopped. We kept going to the top of the hill, when we got to the top of the hill, it had like a double top. When we got to the top there was a small valley like that and it went up again to another small hill. And the strange thing was in the valley, there was a North Korean platoon having their breakfast. They were eating rice out of baskets. All that noise and fire that had been going on, they were calmly eating their breakfast.

So, Paddy O’Sullivan, he set up on our command. We went down into this valley and Paddy went down with two bullets in his groin. Big Bob Sweeney took command and we followed Bob up to the second hill where a number of that Korean platoon had been eliminated. They’d retreated back up to the second little hill and we were climbing up that toward, and they were throwing grenades down at us, shooting small arms fire. Eventually, we captured the top of the hill. Because of that action, Corporal Sweeney won a military medal.

Then suddenly, two aircraft appeared. They went over the top of our heads. We thought at the time, in that minute, that they were going to attack this gully where the North Korean Army was coming up, and four platoon and five platoon were trying to hold them back. And as I sat there watching this aeroplane, it dropped this thing, I didn’t know what it was and it was a napalm bomb. And it dropped on the top of four platoon and five platoon, it just went like that. I were later led to believe we had sixty casualties in two minutes. The end of the day we had ninety casualties and it just decimated them two platoons.”

The 27th Infantry Brigade advanced North in pursuit of the retreating North Korean Forces and was joined by the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment who had arrived in early October. The brigade was renamed 27th Commonwealth Infantry Brigade to reflect the origins of the troops that were part of it.

They moved to within forty miles of the Yalu River, which formed the border with the Communist People Republic of China. In late October 1950, concerned over the proximity of United Nations forces to her border and to support the North Koreans, communist China joined the war.

Pouring thousands of troops into the Korean peninsula, the Chinese offensive quickly pushed United Nations forces into a fighting withdrawal southwards.

Retreat

Between November 1950 and January 1951, Chinese forces relentlessly advanced southwards, crossing the 38th Parallel and capturing the South Korean capital Seoul on the 3rd January. During the retreat, 27th Commonwealth Infantry Brigade operated as a rear-guard force protecting United Nations forces trudging southwards in extreme winter conditions, until relieved by newly arrived, 29th British Infantry Brigade.

In the north of the country, Marine Andrew Condron was with a small force of Royal Marines, 41 (Independent) Commando, ho had been attached to the 1st US Marine Division around the Chosin Reservoir area.

Surrounded by Chinese forces, they were forced to withdraw towards the port of Hungnam and during a freezing 17 day retreat under constant attack, sustained a number of losses and had some personnel were made prisoners of war.

‘It was a very confused and chaotic situation’

“They mortared one of the tracks up ahead and they mortared one or two trucks at the back, effectively blocking the road at both ends. And then they just gradually closed in and quite a considerable number of our people got through. At the end it was the last, I don’t know, the last twenty trucks or so, or something like that got caught. At first, we just stayed on the trucks and, well, there were a few bullets fizzing around and I presume there was a number of people hit. When the trucks finally ground to a halt we were ordered off the trucks and at both sides of this little road we were on was a small kind of monsoon ditch running up on both sides. So, we just got into this little ditch or trench on either side. You couldn’t always see the enemy on a hillside. You occasionally saw them ducking from foxhole to foxhole, but there weren’t, sort of, masses of them, it was all, it was a very confused and chaotic situation.”

Final stand: 1951

In early 1951, the United Nations force launched a series of counter offensives and re-crossed the 38th Parallel. But on 22 April, the Chinese Spring Offensive began

Chinese forces crossed the River Imjin and began to attack the forward positions of 29th Infantry Brigade. Massed infantry assaults penetrated the deep into the British defensive line threatening to envelop the brigade positions strung out along a line of hills, to the south of the river.

The 1st Battalion, Gloucestershire Regt took the brunt of the Chinese attacks and began to withdraw from their positions during the morning of 23rd April, making for the Hill 235, later known as ‘Gloster Hill’.

Here surrounded by Chinese forces and cut off from the rest of the 29th infantry Brigade, the battalion made a final stand and held their positions on the hill for two days in the face of fierce attacks.

The Chinese employed ‘human wave’ tactics, massed frontal infantry attacks, playing bugles and banging gongs to disorientate defenders.

On the morning of 25th April, running low on ammunition and having suffered many casualties the commanding officer of the battalion, Lieutenant-Colonel James Carne, ordered the survivors to make their way to the British lines. Only a handful of them were able to do so.

The people who did not make it back to British lines – including Lieutenant-Colonel Carne- were captured and endured two years in Chinese captivity. For his leadership during the desperate defence of ‘Gloster Hill’, Carne would be awarded the Victoria Cross.

Private Anthony Eagles was chosen to stay behind on Hill 235 to cover the wounded – in this clip he remembers the important role the battalion’s bugle player had.

‘Play anything you like bar a retreat’

“I think it was about ten o’clock we were told that we had been selected to stay and give cover and fire to the rest of them as they went out and we were to stay with the wounded. So, we took up our positions in front and round the wounded but we didn’t have much to go. And then when everybody had gone off, the Intelligence Officer, Henry Cabral said, ‘Come on lads, what have you got?' Well, I had about three rounds, I think. And the others were in a very similar state, you know. So, I said well, what we’ll do is, we’ll just loose off one here and then move and then loose off one there, just move around to make them think there were more of us here than there was. And then when we finished what we had left he said ‘Right, you can smash up your rifles,' so we took it to pieces and smashed it up. I got my bugle. I was the only one that still had the bugle because I had taken it down to Pusan. And Tom in fact had played it in the early hours. The Colonel said to him, ‘Have you got your bugle with you?’, and he said, ‘Well, yes,' he knew I had one. He said, ‘Would you play it? Play anything you like bar a retreat.’ So Tom Major was a very beautiful bugler, lovely to listen to and he excelled himself that night playing. And it stopped the Chinese bugles in their tracks.”

Wounded

Further eastwards, 27th Commonwealth Infantry Brigade held positions in the Kapyong Valley. Again facing large numbers of Chinese troops, the Australian and Canadian battalions that made up the brigade endured fierce attacks on Hills 504 and 677 after the South Korean forces in the north of the valley retreated under intense Chinese pressure.

Private Pat Knowles of the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment was a stretcher bearer during the Battle of Kapyong. He recalls transporting a man who had been injured when a US Marine Corps aircraft accidently dropped napalm on the area.

Over three days the Chinese repeatedly attacked, forcing the Australians to withdraw from Hill 504 on the evening 24th April 1951.

Such was the strength of the resistance and the casualties inflicted, that the attacking Chinese division was forced to retreat to the north of the valley on the 25th April.

‘They give you a stretcher’

“They give you a stretcher and there’s a blanket over the entire stretcher. And they said now, ‘hold onto the handles and the blankets as hard as you can’, which we did. This guy said to me, ‘please give me a drink of water, mate’, and I said, ‘look, we’ve got no water and secondly, we’ve been instructed not to give you any water.’ After a few minutes he repeats this. A few minutes later the blanket is torn right out of my hands and there I’m looking at a man that’s been fully barbequed. His nose, his ears, his lips, his hair, his eyebrows, they’re all gone. He’s really barbequed. And he said to me, ‘please, for Christ’s sake mate, give me a drink.’ And I said, ‘well, I told you before, we’ve got no water and if we did, we’re not allowed to give you any.’ So, with that he accepted that, so we carried him the rest of the way. Anyway, although two of the other napalm victims died, he lived alright, he survived alright. And I learnt many years later they did a first-class job reconstructing his face.”

Trench warfare

The actions of 29th Infantry Brigade and 27th Commonwealth Brigade on the Imjin River and during the Battle of Kapyong effectively blunted the Chinese Spring Offensive, allowing United Nations’ forces to re-group and form a defensive line north of Seoul.

In July 1951, 1st Commonwealth Division was formed encompassing all Commonwealth units serving in Korea and this coincided with the start of armistice negotiations at Kaesong.

The next two years, as the armistice negotiations stalled, became a period of static trench warfare with both sides, primarily acting in a defensive role, using limited tactical operations to exert pressure at the negotiations.

As the front stabilised in late 1951 and for the next two years the war took on many features of First World War trench warfare, during that period many British and Commonwealth units served in the front-line in a defensive role. The two sides, usually entrenched on hilltops, were divided by a non-man’s land, in some places miles apart, in others only a few hundred yards wide. Hilltop positions were extensively fortified with trenches and barbed wire, covered by machine gun positions and supported by artillery.

Night time patrolling and trench raiding became the preferred tactic, with patrols ranging across no-man’s land, aiming to ambush or attack exposed positions. The weather also became a factor, the Korean peninsula experiencing extremes of cold in winter and searing heat during the summer with a short monsoon period, when torrential rainfall often flooding the front-line trenches.

Captain Alberic Stacpoole of 1st Battalion Duke of Wellington’s Regiment recalls the challenges of patrolling and living in the ‘hutchies’, the dugouts where British and Commonwealth troops patrolling and living in sometimes very harsh conditions.

‘That was not quite amusing always’

“It was really terribly, terribly cold, and I remember being out on patrol and we went to ground for just twenty minutes. And in that time, we froze to the ground and our light machine guns and our moving parts of automatic weapons all froze. And you had to keep sliding them quietly for your own circulation of your body and also to keep your weapons circulated, otherwise they simply froze stiff. And as you tired to get up off the ground all your clothes would be sticking to the ground with that kind of white, dry ice because it was 20 degrees below zero or something and it could be terribly cold. We had space heaters which were in the living hutchies and things, which were essentially a large open space like a huge saucepan, one of those pressure cookers, into which one dripped naked petrol. And that burned away inside and got these things glowing and it just burned a straight petrol at a drip speed. And they were fine in a way if they worked, but they didn’t always work and some of them went up in flames and then you would suddenly see in the middle of sort of a serious bit, when you knew patrols were around, you would see a living hutchie going up in flames and people running out and rescuing their sleeping bags and all the rest, which were perhaps on fire. And that was not quite amusing always. And people sometimes did get properly burned on those occasions with accidents with petrol like that. But as a system it seemed to be the perfect answer.”

Armistice: 1953

An armistice agreement was signed on 27th July 1953 at Panmunjom, the two sides finally reaching agreement on the location of the border and the creation of a demilitarised zone along its length.

No peace treaty has ever been signed and Korea remains divided into North and South today.

The Korean War saw the largest commitment of British and Commonwealth troops since the end of the Second World War and the highest number of casualties. In total, 1139 British personnel, 516 Canadians, 340 Australians, 35 South Africans and 33 New Zealanders lost their lives between 1950 and 1953.