On 8 May 1945, the Allies celebrated VE Day, marking the end of the war in Europe. But the war in the east still raged on and Japanese surrender seemed a long way off.

War against Japan, 1945

In South East Asia, by late 1944, British and Commonwealth, US and Chinese forces had begun the reconquest of Burma (Myanmar). The main attack was carried out by the Fourteenth Army, comprising 340,000 Indian troops, 100,000 British and 80,000 African soldiers, which defeated the Japanese defending forces in central Burma. The capital Rangoon was retaken in May 1945.

In China, Operation Ichigo started in April 1944. It was the largest Japanese campaign on land during the war comprising 500,000 troops. The provinces of Henan, Hunan and Guangxi were taken and by October 1944 Sichan was the last large province still held by the Chinese Nationalists. The offensive was finally halted in December. Over 14 million Chinese died during the war, of which 2 million were battlefield casualties.

In the Pacific, Japanese expansion had been checked by US forces in a costly island-hopping campaign. The capture of the Mariana Islands in November 1944 meant that air bases could be established to bomb Japan. The remaining Imperial Japanese Navy was wiped out at Leyte Gulf off the Philippines, which was liberated in early 1945. Then in February 1945, US Marines assaulted the tiny island of Iwo Jima, midway between the Marianas and Japan. Casualties were high, but the island provided another useful staging post for the bombers.

Battle for Okinawa

The last great island battle of Okinawa began with an onslaught of shells, rockets and bombs from 1300 ships (the British Pacific Fleet also took part). The fighter-bombers from 40 aircraft carriers made 3000 trips to bomb the island and the big guns of ten battleships and nine cruisers fired 13,000 shells. The Japanese staged a furious defence, which included kamikaze suicide attacks (c. 1900 sorties) against the invasion fleet. The Americans lost 36 ships. The defending forces of 77,000 troops (and 20,000 Okinawan militia) largely hid in the caves during the bombardment which withstood all but a direct hit to the entrance, with the resulting raising of Japanese morale. Whereas the civilian population without this protection died in their thousands.

On 1 April 1945, four US divisions landed on Okinawa; the fighting became a war of attrition that lasted almost three months for an island the size of 485 square miles. Mutual support was essential in defence and attack by either side. American support included Sherman tanks armed with flamethrowers. These flamethrowers were used to drive Japanese defenders from their caves and pillboxes. There were two unsuccessful Japanese counterattacks which ultimately weakened the capability of the defending forces to resist the American onslaught. However dismantling the Japanese defence, built on taking one cave at a time, resulted in almost 8,000 American deaths. More than 170,000 US servicemen took part in the island’s capture, it was the most costly operation in the Pacific war.

Bombing raids and plans for the invasion of Japan

The first firebombing attack was on Wuhan, the Imperial Japanese Army headquarters in China, on 18 December 1944. Bombs filled with a new incendiary made of phosphorous and napalm were dropped on the city causing a firestorm that lasted several days causing tens of thousands of deaths. The B-29 Superfortresses were then withdrawn from China to bomb Japan from the Marianas. Initially the US undertook daylight precision bombing raids, but on the nights of 9-10 March, a change of strategy began with low level mass incendiary attacks on Japanese cities. This raid burned 15.8 square miles of Tokyo, killing almost 100,000 Japanese. By the end of the war, these bombing raids burned 66 cities, destroying 20% of the housing and leaving about 15 million homeless. About 400,000 Japanese died as a result of these raids plus the dropping of the atomic bombs.

In the planned invasion of Japan, the US navy planners favoured the blockade and bombardment of Japan to instigate its collapse. General Arthur MacArthur and the army planners urged an early assault on Kyushu followed by an invasion of the main island of Honshu. Admiral Chester Nimitz agreed with MacArthur. The ensuing Operation Downfall envisaged two main assaults – Operation Olympic on Kyushu, planned for early November and Operation Coronet, the invasion of Honshu in March 1946. The casualty rate on Okinawa was 35%; with 767,000 men scheduled to participate in taking Kyushu, it was estimated that there would be 268,000 casualties. The Japanese High Command instigated a massive defence plan, Ketsu Go (Operation Decisive) beginning with Kyushu that would eventually amount to almost 3 million men with the aim of breaking American morale by ferocious defence.

Atomic Bomb

On 26 July, the United States, China and Great Britain issued the ‘Potsdam Declaration’ calling for the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces and the occupation of Japan by the Allies. There was no mention of the Emperor in the declaration as public opinion was not in favour of his retention, although it had previously been decided in committee. However the declaration failed to shake Japanese hopes for Soviet mediation.

The race to produce the first atomic weapon before Germany was headed by the Manhattan project. It consisted of more than 120,000 people working on 37 different sites across 19 states in the US and in Canada, at a cost of more than $2 billion. All of which resulted in the first atomic bomb test carried out at the Alamagordo Air Force Base, New Mexico on 16 July 1945. President Harry Truman received news of it whilst at the Potsdam Conference. With the apparent rejection of the Potsdam Declaration, Truman and his advisers went ahead with the atomic attack on the Japanese mainland.

On 6 August the lead bomber of three B-29s, Enola Gay, piloted by Colonel Paul Tibits, commander of 509th Composite Group, dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Close to 66,000 people were killed. It was followed by a second bomb on 9 August on Nagasaki. About 39,000 were killed. As at Hiroshima, thousands more were to die from their injuries or the after-effects of radiation.

Soviet Invasion of Manchuria

Stalin had agreed to enter the war against Japan at the Teheran Conference in 1943. At the Yalta Conference in February 1945 the Allies agreed to the Soviet conditions which included restoration of her special rights in Manchuria after their defeat during the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-5. However the reality of the atomic bomb made some US leaders question whether Soviet intervention in Asia was indeed needed or even desirable. The Soviets informed the Japanese in April that their neutrality pact was at an end. At Potsdam the Soviets informed their Allied counterparts that they would be ready to move against Japan in mid-August.

Stalin brought forward the invasion of Manchuria due to the dropping of the atomic bomb. On 8 August the Soviet Union entered the war against Japan at midnight. Soviet forces invaded the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo (Manchuria) under the command of Marshal Aleksandr Vasilevsky with 1.6 million soldiers. They achieved complete surprise, outgunning and outflanking the defending Japanese Kwantung Army of 713,000 troops, commanded by General Otozo Yamada. The advancing Soviets claimed to have killed 84,000 Japanese soldiers and captured almost 600,000. About 1.5 million Japanese in Manchuria, Korea and northern China became prisoners of the Soviets, many of whom spent years in prison camps.

Japanese Surrender across Asia

Emperor Hirohito, in a meeting with his Imperial Council, stated that he wished to surrender as long as the role of the emperor was not compromised. On 10 August Japan offered to surrender unconditionally under the terms of the Potsdam Declaration as long as the emperor remained sovereign ruler. The next day a reply was drafted by the US which insisted that any imperial authority would be in the hands of the Supreme Commander of the Allied powers. On 14 August Japan surrendered. The capitulation followed three days of heated debate amongst Japanese leaders. The military leaders were for outright rejection of the Allied surrender, as it did not guarantee the Emperor’s sovereignty. Emperor Hirohito summoned an Imperial Council asking that his ministers accept the terms forthwith and surrender unconditionally. Members of the imperial family were despatched across China, Manchuria and South East Asia to convey the Emperor’s desire for an orderly surrender at his personal behest.

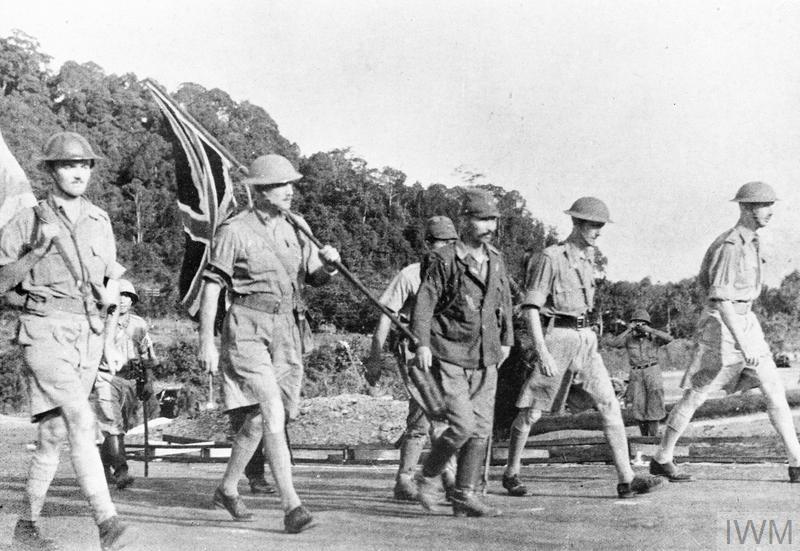

A number of surrender ceremonies took place across South East and East Asia culminating on 2 September when the formal instrument of surrender was signed by Allied and Japanese representatives on the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. General Umezu Yoshijiro, the army chief of staff, signed on behalf of the Imperial Japanese Army in front of the newly appointed Supreme Commander, Allied Powers in Japan, General Douglas MacArthur. In the Allied party were Generals Percival and Wainwright who had surrendered to the Japanese in 1942 at Singapore and in the Philippines respectively. They and their soldiers had endured three years of harsh captivity.

Alan Jeffreys

Senior Curator