In January 1942, the Japanese Army invaded Burma (now called Myanmar). The Japanese faced weak opposition from the Allied forces defending the vast Burmese frontier.

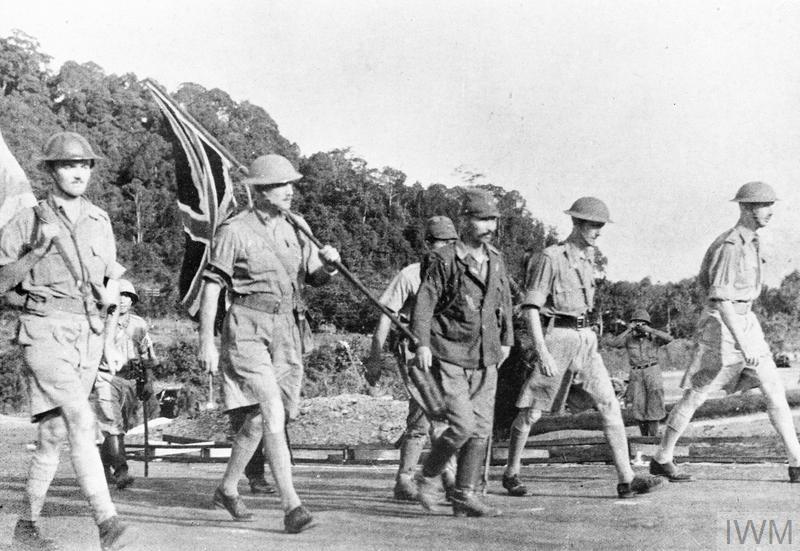

Allied troops endured over three years of brutal fighting, often in extreme terrain and menaced by severe weather and the threat of disease. Allied troops, led by Britain's Indian Army, reoccupied Burma in 1945.

Listen to 8 people describe their experiences of the Burma Campaign during the Second World War.

1. The Battle of Sittang Bridge

Neville Hogan was serving with the Burma Auxiliary Force when the Japanese invaded the country in early 1942. The defending force consisted only of two under-strength regular British battalions, two Indian Army infantry brigades and local Burmese forces. Using already proven tactics of infiltration and mobility, the Japanese advanced rapidly, trapping two Indian brigades in a bridgehead on the east bank of the River Sittang after the bridge across the river had been prematurely blown. During the battle which followed, the Japanese won a decisive victory. Hogan recalls swimming the fast flowing River Sittang after the destruction of the bridge left him stranded on the south bank.

Neville Hogan interview

© IWM (IWM SR 12342)

'But once you get there, underneath, oh it's frightening'

"I think parties of about 30 or 40 were organised to swim this river. And I was in one of these parties. Coming down a swift flowing river is something. It’s frightening. You look at water, it’s so beautiful, but once you get there, underneath, oh it's frightening. Boots around my neck, a 4.5 pistol with its big web belt, a big broad web belt choking you. Tin hat, which I lost immediately I got into the water, a pair of shorts and that's it. About half way, three quarters of the way across, I had a thud in my thigh and I thought, ‘Oh God, there goes another poor Gurkha drowning.’ But it turned out that I was hit by shrapnel in my thigh. Anyway I got to the north bank about 300 yards from the bridge, climbed up. Out of our party of about 30 or 40 – I'm not quite sure – there must have been about only 10 of us left. And then we made for the railway line which takes us to Pegu. We got to Pegu which was about a 42 mile walk and I think we did that in about 2 days. And there was a hospital train where I had my shrapnel removed just by being pulled out, leaving a few bits inside…"

2. Retreat and evacuation

As the Japanese advance into Burma gained momentum, British reinforcements began to arrive. But they couldn't prevent the fall of Burma's capital city, Rangoon, or of Mandalay, Burma's second city. British and Empire forces under Generals Alexander and Slim began the long and tortuous withdrawal to India. In what became the longest fighting withdrawal in the history of the British Army, the retreating troops faced problems of sickness and disease, impenetrable jungle, poor roads and constant harassment from the Japanese Air Force. They shared the retreat with thousands of civilian refugees fleeing northwards to India to escape the threat of Japanese brutality. The last stragglers crossed the final mountain range into India at Imphal in May 1942. Prue Brewis was serving with the Women's Auxiliary Service (Burma) at the time of the invasion. She was one of the thousands who fled Burma for India, in a long and exhausting journey.

Prue Brewis interview

© IWM (IWM SR 22741)

'We were absolutely packed like sardines'

"We had to evacuate rather quickly. We were taken to Shwebo by about 9 o'clock at night. And then we were put on the train. Very hot. There were 8 of us in a carriage. We were on this train for 6 days and did exactly 65 miles in 6 days because we could only travel at night. Anyway after 6 days the… I don’t know what he was, the director of railways, came down in his rail car. So he gave us 10 minutes to sort out what we thought was about 30 pounds of luggage and get into his rail car where we were absolutely packed like sardines. Standing up, standing room only, you know. And took what we thought was most essential things, really, anything we wanted to get out. And he took us the other… I don’t know how many miles, 100 miles or something, up to Myitkyina. And actually we got the last plane to leave Burma because the next day the aerodrome was bombed. Well we flew out and then we went on a train journey down to Calcutta where we had to try and buy a few clothes and then were sent on to Simla."

3. Operation 'Longcloth'

In September 1942, the Indian 14th Division launched a failed campaign to recapture the Arakan coastal plain in western Burma. The Japanese put up a strong resistance and the campaign fizzled out after a series of setbacks and retreats early in 1943. With the failure of this offensive, British Brigadier Orde Wingate was given permission to mount a long-range raid behind Japanese lines. Wingate's raiding force became known as the 'Chindits'. The first Chindit Expedition, Operation 'Longcloth', was launched in February 1943. The Chindits suffered high casualties, and much of the damage they inflicted on Japanese rail communications was rapidly repaired. But the operation delivered a much-needed boost to demoralised Allied troops. In March, Wingate ordered the Chindits to withdraw. Dominic Neill was an animal transport officer with 8 Column during the expedition. He describes being ambushed during the retreat by Japanese troops on 14 April 1943.

Dominic Neill interview

© IWM (IWM SR 13299)

'Hundreds of thoughts flash through the minds of those caught in this way and all in the briefest of seconds'

"We were now marching north along a narrow track. I had about two or three Gurkhas ahead of me and the others to my rear. I don't think we'd gone very far out of the village when, totally out of the blue, an ambush exploded abruptly to my immediate left. I can remember roaring out to my men, ‘Take cover right’ before diving for cover myself into the bushes to the right of the track. Things happen very quickly in an ambush, hundreds of thoughts flash through the minds of those caught in this way and all in the briefest of seconds. I remember that I wasn't actually frightened, which surprised me, but I was totally and utterly shocked. Never ever during any of my previous training had I been taught any of the approved contact drills, certainly the counter ambush drill was unknown to me. I was utterly appalled to realise that I simply did not know what to do in order to extract my men and myself from our present predicament. My earlier inadequate training chickens had now come home to roost with a vengeance. The gunner was firing his LMG immediately opposite me from the jungle on the far side of the track. He was so close that I could clearly see the smoke rising from his gun's muzzle. His bursts of fire were hitting the trees and bushes above my head, the bullets were cutting the branches and bits of leaf and wood were falling on my pack, on my neck and down my shirt collar. There was also rifle fire coming from the enemy lying to the left and right of the light machine gunner. I think, but I'm not absolutely certain, that another LMG was firing at my men who had been behind me on the track. Altogether my impression was the enemy ambush was not of any great length."

4. Mules and supplies

During the campaign, mules became the preferred method of transporting supplies over Burma's difficult terrain. Bordered by India, China and Thailand, the country is surrounded by jungle-covered mountain ranges and divided by several major rivers. Its monsoon season affects roads and communications, and the climate produces dangerous wildlife and the threat of disease. Wingate's Chindit force included 1,000 mules, essential for negotiating the country's jungles and water-logged ground while laden with provisions for the troops. Roland Nappin, a muleteer with 2nd Battalion, Welch Regiment, describes the problems he encountered when loading mules in 1943.

Roland Nappin interview

© IWM (IWM SR 20593)

'They were looked after well and truly'

"I can't remember the exact company I was with but they wanted volunteers for to go into the animal transport. And I volunteered and that was how I became a muleteer. I liked animals and I thought it would be something different and I volunteered for the animal transport. So I ended up as a muleteer. When I joined the animal transport, the mules that were there, we had to put saddles on them and that was a job of itself. You'd get the saddle on and tie the girth around and as soon as you went to put a load on them to carry they used to up, buck, hind legs up in the air and throw the load off. The one I had did this, so we tied him up tight to a post, held on to him, put the blankets on him, threw a girth all over the lot so he couldn't throw it off and then we took him round. He was bucking and chucking and trying to throw it off. He'd come back afterwards white with lather, but he didn't throw any more off, it was just to get them to carry a load. We brushed them down and wiped them down, they were looked after well and truly."

5. Field rations

Indian troops provided the majority of 14th Army's fighting strength during the Burma Campaign. John Randle, an Indian Army officer with the 7th Battalion, 10th Baluch Regiment, discusses the field rations that sustained him and his men during the campaign.

John Randle interview © IWM (IWM SR 20457)

'My endurance and capability to go on fighting through the monsoons and in great heat and stuff was completely sustained by this'

"To start with anyway we had our own mess, our own cook. Later on in the war I switched over to eating Indian food. As the only British officer in the company I mean my ration was a couple of biscuits and half a tin of warm bully beef. So I decided this was ludicrous, so I adapted myself to eating Indian food, I've never been so fit in my life. Looking back on it now I was remarkably fit. Up in the fighting in Burma it was mainly dal, which is lentils, very lightly curried with a bit of ghee and then chapattis, unleavened bread. I believe from a dietary point of view that is as good a food as any. We fought all the way through Burma our chaps, on that, and my endurance and capability to go on fighting through the monsoons and in great heat and stuff was completely sustained by this. Occasionally we liberated a chicken or something like that or a goat, but we didn't even get an awful lot of meat really."

6. Ngakyedauk Pass

In March 1944, the Japanese Army launched an attack on India called Operation 'U-Go'. The Japanese aimed to seize British supplies in Assam, inspire a rising by the Indian populace against British rule, and take pressure away from the US advances in the Western Pacific. It was supported by Operation 'Ha-Go', which was intended to draw British attention away from the Imphal area where the brunt of the 'U-Go' attacks took place.

As the Japanese 55th Division attacked northwards in the Arakan, British forces employed new defensive techniques to counter Japanese infiltration tactics. They held out against determined Japanese assaults until the Japanese, short of supplies, were forced to withdraw. Fighting was particularly fierce around the Ngakyedauk Pass, where British troops fought off a series of attacks. Norman Bowdler was a trooper with the 25th Dragoons, a British tank regiment. He explains the problems of driving his Grant tank over the Ngakyedauk Pass in 1944.

Norman Bowdler interview

© IWM (IWM SR 22342)

'Yes it was a bit dodgy, getting a thirty ton tank around these S-bends'

"Well it was a frightening experience because it was done at night. We were overflown by aircraft all the time to drown out the noise of our engines and we were very close to the Japanese – very close indeed. We had to get over this pass which had just been recently dug I mean it was twisty turny. There would be a drop on one side of five or six hundred feet and on the other cliffs straight up. Yes it was a bit dodgy, getting a thirty ton tank around these S-bends. Some of the bends were so severe that you had to go backwards and forwards, backwards and forwards to negotiate them."

7. Siege of Kohima

The British defensive tactics were again employed on a larger scale when Imphal and Kohima were surrounded during Operation 'U-Go'. In April 1944, one British battalion and some additional garrison troops at Kohima held out for ten days against the Japanese 31st Division until they were relieved by the British 2nd Division. In the fighting they held off over 25 full-scale infantry attacks, suffering very heavy casualties with over 200 men killed. At Imphal a larger perimeter was established, with British and Indian troops defending the surrounding heights. The battles continued at Kohima and Imphal until the Japanese withdrew, having both exhausted their supplies and suffered heavy casualties. Bert Harwood served as Sergeant Major with C Company, 4th Battalion, Royal West Kent Regiment during the siege of Kohima. He describes the conditions for the wounded during the battle.

Bert Harwood interview

© IWM (IWM SR 20769)

'The shelling killed people that were in the trenches, waiting'

"The casualties were taken back into battalion headquarters, they had pioneers and that there, they dug all these trenches to lay the wounded in, nothing over the top of them, just laying them in there. I walked around there one day just to see how some of the blokes were and it was terrible really seeing them laying out there just in these trenches. We were supplied by air at that time. These parachutes came down and water was one of the main things we had trouble with and they used to drop these water packles, the packles which were carried on the side of a mule, you used to carry one on each side of a mule, water. They were dropping these down by parachute and on occasions the parachute wouldn't open and one of these packles hit a couple of casualties in the trenches and killed them. That sort of thing happened. The shelling killed people that were in the trenches, waiting. Even the actual first aid centre, I never actually went into it, I went round where the casualties were, but eventually that got hit by shells and I think a doctor was killed. They were doing all operations with the very minimum of supplies."

8. Japanese surrender

By the end of 1944, the Allies were ready to advance onto the central plains of Burma. Employing new tactics, using a combination of tanks and infantry, long columns advanced southwards, destroying Japanese resistance. Amphibious landings allowed forces to advance along the Arakan coast. Mandalay was captured on 20 March 1945 by 19th Indian Division. Two months later Rangoon fell and Japanese troops retreated to the River Sittang. In August, atomic bombs were dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Soon after, Japan surrendered. The war in the Far East was over. Enid Grant was a British nurse who served with the Burma Hospital Nursing Corps between 1942 and 1945. She describes how VJ Day was celebrated in Rangoon in August 1945.

Enid Grant interview

© IWM (IWM SR 22688)

'There was money; I picked up a lot of Japanese money which was thrown'

"We then got posted to Rangoon. I can't remember, I think we were flown by RAF plane to Rangoon. I was there on VJ Day. We were put in the YWCA to start with there was no particular hospital posting. And VJ Day came while we were there – it was very exciting. All the shipping on the river tooted and hooted and sirens were everywhere and people were rushing up and down the streets in jeeps. There was money; I picked up a lot of Japanese money which was thrown. It was just lying about in the streets. And we all dashed about and somebody tried to drive a tank into Government House and the Japanese were in there handing over the sword and General Stopford was there. It was a hilarious time, everybody was going about… I had two Japanese notes and everybody around signed them, we all signed these notes. Yes, it was very exciting."

This article was edited by Kate Clements. Other IWM staff members contributed to writing an older version of this piece.

Calling Blighty from Burma, 1945

"Here are the Brighton Boys from Burma with a few words. Hello dears, all my love to you, especially Nina. I'm okay but longing to see you all again."

Michelle Kirby: So you're about to meet the Brighton Boys. They are a group of British Army soldiers who served in Burma during the Second World War. The year is 1945 and the war is not quite over yet, so these individuals have been asked to step up to a camera and to speak from the heart; they're being asked to record personal messages homes their loved ones back in Britain.

"Cheerio now, all my love, keep smiling."

"Hello Mother! Hello Dad. Hope you're keeping both very fit, and that goes for the rest of the family out near Horsham too. As you can see, I'm pretty well and still got something to laugh at. Give my love to Vera, Peg, Kenneth and Pat and tons for yourself. Cheerio for now! God bless you all and keep smiling! Get cracking Ninja."

MK: The series as a whole was produced by the Directorate for Army Welfare in India and the purpose was really to raise morale. There was growing concern around this time that these troops that were thousands of miles from home were fast becoming the forgotten army and the idea was to try to improve communication with home. One of the things that I find really fascinating about the Brighton Boys film is you can feel that palpable sense of separation and yet there is this incredible spirit and camaraderie amongst them, the determination to get through it and be positive. Just count the number of times that they say 'keep smiling'.

"It won't be long now, cheerio all of you! Come on Mike!"

"Hello Mum and Dad, my only thing is to wish Eileen and John the best of luck and hoping to be back with you all again in England soon. All of us boys here are going to win the war and get back to you all a bit jolly So cheerio darling and keep smiling. Come on John!"

Once they were done filming the Brighton Boys would be asked by the welfare officer who out of your family and friends do you want us to write to, give us their addresses and we're going to invite them to a special screening at a cinema somewhere in the Brighton area and they were going to bring all of the family and friends of all of these boys together under one roof to hear these special personal messages. Sometimes it took as long as 12 weeks for those films to get from the point of filming the boys to actually up there on the cinema screen but it was well worth the wait. Can you imagine how emotionally charged those cinemas must have been, I mean some of these families wouldn't have seen the faces of their loved ones for potentially years. They must have been full of laughter and tears of joy, and sometimes also tears of great sadness, because we do know that across the Calling Blighty series there were some individual servicemen who were very sadly killed in action after being filmed.

"Take care of yourself, cheerio for now. Come on George!"

"Hello Hilda darling, hello champ I bet you never expected to see me as a film star but here I am. I'm feeling very fit and glad to know that you're both the same. Remember me to all at home. Of course I miss you both a terrible lot but until that day I can get back to you, keep that chin up and keep smiling

Give mum a kiss champ! Cheerio!"

For me, the Calling Blighty series and particularly the Brighton Boys films really show the power of film, the power of seeing someone and hearing someone. It's kind of interesting that we're in such an unusual global situation now and yet many of us are seeking comfort from video contact, from video calls with our loved ones, and it turns out that nearly a century ago the power of moving images was also used to bring together people who were divided.

"Come along Sam!"

"Hello Freda darling, here's proof that I'm safe and well and if our families are watching this, you want to tell them to get their money back because I'm not worth it. Look after yourself and keep smiling. I just wanted to give three cheers from the Boys from Brighton before we finish. Right boys, three cheers.

Hip hip, HOORAY! Hip hip, HOORAY! Hip hip, HOORAY!"