Armistice

By the autumn of 1918 the German Army was on the brink of collapse and Germany itself was in political turmoil. Realising that the war was lost, the German government approached US president Woodrow Wilson on 4 October and asked him to broker a ceasefire with the Allied powers. Wilson’s Fourteen Point peace plan, first proposed in January 1918, was to form the basis for negotiations.

But events were moving rapidly. Within weeks of the request armed revolution in Germany led to the collapse of the government and the abdication of the Kaiser. On 9 November a socialist republic was proclaimed. The following day representatives of Germany’s new government and the Allied powers met in a railway carriage in the forest of Compiegne to discuss terms.

In reality, Germany was in no position to negotiate. The Allies, led by French supreme commander Marshal Ferdinand Foch, drafted the terms of an Armistice which the German delegation agreed to at 5am on 11 November 1918. At 11am the Armistice came into effect and all along the Western Front the guns stopped firing. Although officially only a 36 day ceasefire, there would be no renewal of hostilities.

At the front, reactions to news of the Armistice varied from euphoria to indifference. Many soldiers were too emotionally and physically exhausted to take in the enormity of the event. Others were sceptical about the war ending so suddenly and found it difficult to believe that the fighting would not resume at some point.

In Britain, rumours of an Armistice had been growing over the previous week. On 11 November, a Monday, crowds began to gather in streets and public places across the country, waving flags and singing patriotic songs. At 11.00am a cacophony of maroons, sirens, factory hooters, train whistles and car horns erupted. The immediate lifting of many wartime restrictions was celebrated with rockets, bonfires, street parties and the ringing of church bells.

Making the peace

With the war over, the business of shaping the peace began. A Peace Conference was held in Paris between January 1919 and January 1920 at which separate treaties were drawn up with each of the defeated nations. As with the Armistice, it was the victorious allies who decided the terms and conditions to be imposed. The most significant treaty was the one with Germany. It was signed in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand at Sarajevo, the event that led to the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914.

The Treaty of Versailles departed radically from President Wilson’s Fourteen Point peace plan. Among the Treaty’s key conditions were a drastic reduction in the size of the German Army, the appropriation of the German Navy and Air Force by the Allies and the prohibition of future ship, tank and aircraft construction. Germany was also stripped of large areas of territory, not least the important Alsace-Lorraine region, which was ceded to France.

But it was Article 231 of the Treaty, the so-called ‘War Guilt Clause’, that was to prove the most controversial. This stated unequivocally that Germany must assume full responsibility for the war and imposed punitive reparations amounting to some 132 billion gold marks. This provoked widespread resentment and economic hardship and proved a significant factor in the growing popularity of Hitler’s Nazi Party during the 1920s and early 1930s.

On a global scale, the First World War led to the rise of the United States as a world power and the disintegration of the German, Russian, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires. New nation states were created in Europe and the Middle East, but this often had the unwelcome consequence of sowing the seeds for future conflicts. The League of Nations, founded at the end of the Paris conference in January 1920, attempted to address these problems and prevent another world war, but ultimately was unable to do so.

Legacy of the war

The First World War cost Britain and its Empire nearly a million dead, and more than twice that number wounded. Over 2,000 civilians were also killed on the home front in air raids, naval bombardments and industrial accidents.

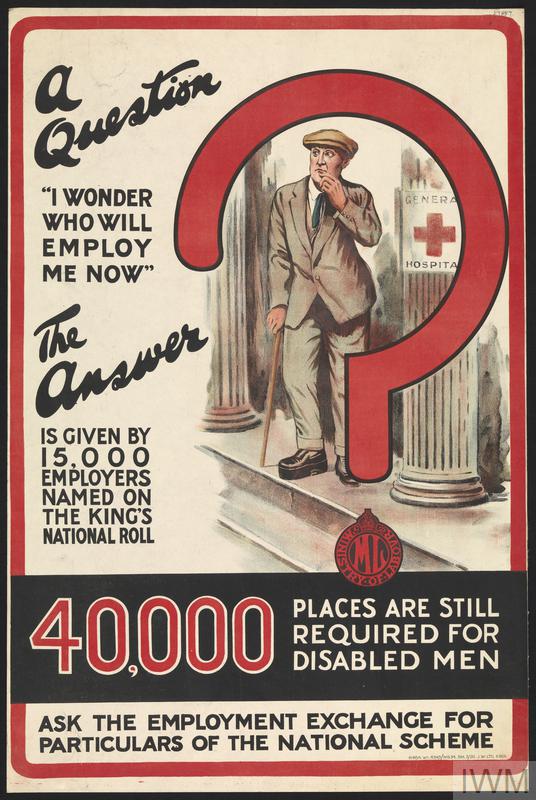

Veterans returned home to find their world had changed. Many felt alienated from civilian life, and joined veterans’ associations to maintain the bonds of comradeship forged during the war. Difficulty in readjusting to civilian life, financial hardship and unemployment were common problems.

But for those disabled or mentally scarred by their war service, the challenges that lay ahead were even greater. Over 40,000 British servicemen returned home from the war having lost one or more limbs and nearly 3,000 suffered partial or total loss of sight. An estimated 80,000 men were also treated for shell shock during the war, some of whom would remain traumatized for the rest of their lives.

Never before had the country experienced losses on such a scale. In the immediate post-war years more than 74,000 local war memorials of various types were created. At a national level, the Cenotaph and Tomb of the Unknown Warrior were designed to honour all the dead, including the tens of thousands whose bodies were never found.

These memorials and the vast cemeteries in France and Flanders are a permanent reminder of the First World War and its legacy.

In 1917, while the outcome of the war was still far from certain, Prime Minister David Lloyd George established a Ministry of Reconstruction. Its purpose was to co-ordinate government departments planning for post-war reconstruction in key areas such as housing, employment and industrial relations. In December 1918, the first general election for seven years was called. This so-called ‘khaki election’ resulted in a Conservative dominated coalition with Lloyd George remaining as Prime Minister.

But the transition to peace time government was to prove problematic. Although victorious, Britain had incurred huge debts during the war. To make matters worse, in 1919 more than 2 million workers went on strike, many from essential industries such as mines and railways, putting further pressure on an already fragile economy.

Renewal

The demobilization and return home of thousands of troops was also a cause for concern. Delays and resentment over prioritizing certain groups led to protests and mutinies that raised fears of serious civil unrest, even revolution. Promises of a 'land fit for heroes' added to the sense of disillusionment as unemployment rose rapidly during the severe economic depression that lasted throughout 1920 and 1921.

Despite this, radical social reforms were implemented. Even before the war had ended, The Representation of the People Act gave the vote to men over 21 and certain categories of women over 30. Women had made a vital contribution to the war effort but full emancipation was still to take another 10 years. In 1919 the newly formed Ministry of Health was tasked to implement Britain’s first large scale social housing scheme, clearing slums and building large numbers of new ‘council’ houses. The rigid pre-war class system also started to disintegrate and a less deferential, more democratic and critical society began to emerge.

The First World War dramatically changed the political, social and economic landscape of Britain and Europe. But despite initial optimism, it was not to be ‘the war to end all wars’. In 1939, only twenty years after the Versailles Treaty had been signed, Germany invaded Poland and a second, longer and even costlier world war began.