The reliance on the home front by soldiers was near breaking point

You're listening to Imperial War Museums, First World War galleries, podcasts presented by James Taylor, head of the First World War Galleries team.

James Taylor: “In summer 1915, there was a tug of war in Britain over manpower. Soldiers were needed, but so too were skilled war workers who could make sure that the fighting men had plenty of guns and shells. Correspondence on display in IWM London's new First World War Galleries, exposes the tensions between two senior politicians over this issue. Laura Clouting is a member of the First World War Galleries team.”

Laura Clouting: “Two letters, one between David Lloyd George responsible for munitions, and one Lord Kitchener responsible for the army. Both of them are essentially saying we need more men. We need men for the army. We need men for the munitions factories. And you can see there's this tension and they never adequately resolve it. Now, up until the introduction of conscription, there are appeals made to men to stay in their jobs from, for example, the Coventry ordinance work sends out a letter to all of its employees to say please stay in your jobs, you are doing vital war service by staying put.”

James Taylor: “Attempts to show that working in Britain's industries was a valuable contribution to the war effort are also evident in other objects in the galleries.”

Laura Clouting: “There's a poster that we have on display in the new First World War Galleries that shows a soldier and a munitions worker shaking hands and saying we're both as important as each other. You also have men given certificates to carry around in their work passes, saying you are doing war service by staying in an ordinance factory. There's a real determination to show that in fact war service is more than just being a soldier.”

James Taylor: “In spring 1915, senior military commanders in the press had blamed Lord Kitchener's War Office for a shell shortage which seemed to be denying Britain's army the chance of victory. This crisis, played out in public, had far reaching consequences.”

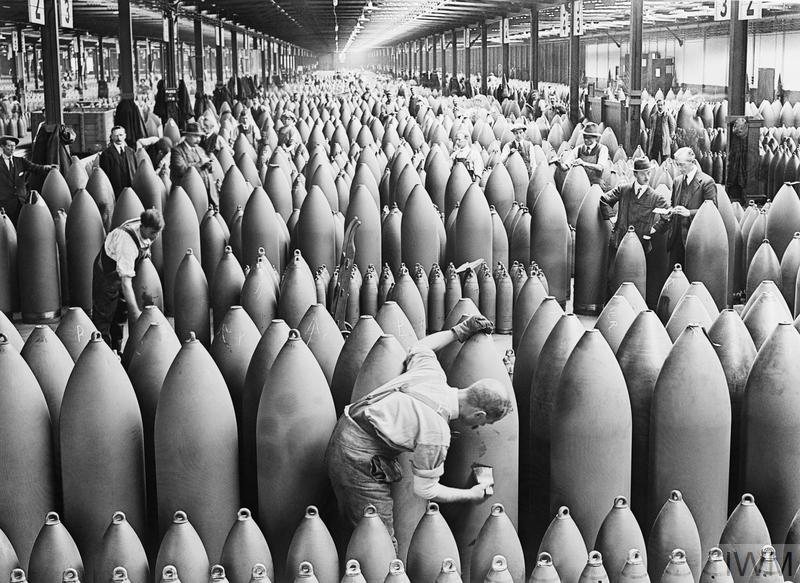

Laura Clouting: “Now this is a scandal. There is immense damage done to the government in the press amongst the men on the fighting fronts who feel let down that they have not had sufficient supplies. And so, the government has an overhaul in itself. It becomes a coalition government, but it sets up this new ministry and it's led by David Lloyd George. Now David Lloyd George goes on to become the Prime Minister in this country, but he has previously been the Chancellor and now becomes this new energetic Minister of Munitions and he sets up brand new factories of epic scale. So, for example, there's a factory up in Gretna on the border of England and Scotland that's around nine miles long with all the different factory buildings that that encompasses. And the types of work going on, well they're making everything from bullets to optics, gun sights to shells, prodigious quantities of shells. Now I personally think the best way to get an impression of the scale of this production of shells is to look at photographs. We have an amazing collection of photographs showing the insides of some of these gargantuan munitions factories and you can see row upon row upon row of shells stacked up in these factories, like Chillwell in Nottinghamshire, and the impression that this gives you is of this vast war machine needing to be fed with these shells.”

James Taylor: “Making shells and actually getting them to the fighting fronts was not a simple process. And for the men and women who worked in them, the munitions factories could be a dangerous environment.”

Laura Clouting: “If you think about the journey that one shell takes, it's fascinating in the sense that a shell case is made in a factory in this country, sent on to another factory to have the explosive filled into it, sent on a train off to a harbour, put on a ship, carried over the water, making it to a train on the other end to take it to the front, to be passed down the line and make it finally to the gun to be fired. It's a huge journey and all of that journey is what we mean by feeding the front. On display in the First World War Galleries is a memorial card to victims of around 73 people who were killed in an explosion at Silver Town in London. The worst loss of life in an explosion was at Chilwell, 134 people died in that explosion and again a TNT explosion.”

James Taylor: “Shells alone could not win the war. Men were still needed to fight. In 1916, conscription was introduced. Those men who still refused to join the army on moral or ethical grounds, known as conscientious objectors, were subjected to terrific hostility.”

Laura Clouting: “In our collection we have a very compelling letter that reveals attitudes towards conscientious objectors in Britain during the war. There's a letter to Mr Harold Visick and it's from an employer Park Davies company who were manufacturing chemists and they're basically turning him down for a job because he is a conscientious objector. Now this letter I have it in front of me just now, a copy of it, and it really lays out quite plainly how conscientious objectors were viewed. In the letter, Mr Visick is told that the logical position I quote “of any conscientious objector is that of a servant of Germany”, and the letter goes on to say, “what do you think are 182 fighting men would think of me if, while they are sacrificing so much I should give employment to someone who not only disapproves of and condemns as unrighteous and unworthy all that they are doing, but is willing to enjoy to the full the protection that their sacrifice alone secures.” It goes on at great length as to why this man cannot be employed by the writer of the letter. But many conscientious objectors are just treated with derision, with really derogatory language in newspapers and in general conversation. The fact is that out of around 2 and half million men who were conscripted from 1916 onwards, conscientious objectors made a very tiny minority. There were around 16,000 conscientious objectors, whereas this other vast number are men who have accepted, if you like, their coercion into becoming soldiers.”

James Taylor: “Feeding the front was not just the work of men, it was also the work of women, many of whom moved in vast numbers, sometimes with their children, to live and work in these huge munitions factories.”

Laura Clouting: “One of the objects on display in the First World War Galleries is a commemorative shell of the first shell made at the Cunard Shell factory, and there women make up something like 80% of the workforce. At factories like Gretna, again, it's women that are in the majority, and these are women who many of them have worked before. There's this kind of idea, I think often, that women have come into these factories, are brand new to the world of work. I wouldn't say that that's the case. It's more that they have never worked in heavy industry before. Many of them have come from things like lace making. And at the start of the war have been made unemployed when those industries have suffered. Now they are being repurposed for heavy industry to directly help the war effort. And there are concerns about their welfare, both in terms of avoiding going to pubs, avoiding falling in with the wrong crowd and also about their children. For example, some factory set up crèches to help women with children. And you also see recreation becoming important. So, women's football teams, for example, are very popular in different factories. So, there's a real effort to try and supervise the welfare of these people, but actually it's to keep these workers productive, that's what matters. It's keeping these people as fit workers to keep churning the stuff out. They are as important as soldiers.”

The First World War Galleries at IWM London are open now. Find out more at www.iwm.org.uk/WW1.

In 1915 Britain faced falling army recruitment and shells shortages at the front. To win the war, a transformation was needed. A ‘home front’ was created to supply the fighting fronts’ constant demands for men, weapons, equipment and food.