The contribution of British women to First World War photography has received little attention in comparison to that of later conflicts. This neglect is mostly due to the prevailing assumption that a war photographer must be a professional photojournalist with access to the battlefield and front line combat. However, such a narrow definition renders a proper appreciation of war photography and its practitioners impossible, particularly with regard to the First World War.

A broader definition is certainly important when considering women’s photography during this period. No professional female photojournalist had access to the battlefield or front line combat between 1914 and 1918. However, in the years since its foundation in 1917, IWM has assembled an extensive collection of professional and amateur photography taken by women for official, commercial or private purposes in the First World War. These photographs offer an important account of the general human experience of the war and a unique feminine perspective. Three collections, comprising photographs by Christina Broom, Olive Edis and Florence Farmborough, are of particular interest for the varied insights which they offer on the war and on the practice of photography by women at this time.

Christina Broom (1862-1939) and Olive Edis (1876-1955) were amongst the first women to build careers as freelance professional photographers in Britain. Both entered professional photography in 1903 in order to earn a living and support their families. Both were well educated by the standards of the day, but were essentially self-taught as photographers. Despite differences in approach and technique, both achieve a combination of formality and subtle intimacy in their photography.

Women Police Service, Knightsbridge, May 1916

Christina Broom: Officers of the Women Police Service, led by Inspector Mary Allen, a former suffragette, maintain order at the Women's War Work exhibition, Knightsbridge, London, May 1916.

Broom worked primarily in London as a freelance photographer from 1903 until her death in 1939. Now recognised as the first woman to style herself a press photographer, she submitted photographs, most notably of the Suffragette movement, to picture agencies for publication in magazines and national newspapers. But the core of her business, and the key formative influence on her photography, was the picture postcard industry, which peaked in popularity between 1902 and 1914. Trading as Mrs Albert Broom and equipped with a medium format glass plate camera, Broom developed an effective style of group photography, shot primarily on location in the open air. Adept stage management and a subtle empathy for her subjects resulted in formal, carefully composed, yet revealing photographs which were often surprisingly intimate.

Broom’s technique lent itself to military and ceremonial subjects. In 1904, an assignment with the Scots Guards resulted in her appointment as official photographer to the Brigade of Guards and Household Cavalry. This unprecedented accolade, sanctioned by King Edward VII, gave Broom unique access to these regiments, regarded as the elite of the British Army, at their London headquarters during the war.

Mrs Albert Broom at the Women's War Work exhibition, London, May 1916

Mrs Albert Broom, self-proclaimed "Official Photographer to the Guards", photographed by her daughter as she displays her camera and examples of her photographs at a stand at the Women's War Work Exhibition, Prince's Skating Rink, Knightsbridge, London, May 1916.

Although it could be argued that Broom’s photography as a whole is somewhat formulaic, this criticism is less applicable to her wartime photography. Her coverage of the regiments preparing to leave London for France in August 1914 is candid, spontaneous and entirely devoid of the patriotic fervour then sweeping the country. Broom had worked with these soldiers for ten years. This was not just a professional assignment. It was a personal farewell to men she knew well and might not see again. Her photographs convey a grim urgency as men gather their equipment and assemble for departure.

Broom’s subsequent coverage of wartime events in the London area is similarly expressive. A group of women police officers, photographed in 1916, are undeniably formidable, and makes a clear point about these former suffragettes who had abandoned their violent political protest of the pre-war years to uphold the law in wartime Britain. A photograph showing a group of Women’s Volunteer Reserve signallers conveys amateurish enthusiasm. Inherent welcome and relief pervades Broom’s depiction of massed ranks of fresh-faced American troops at lunch soon after their long-awaited arrival in Britain. Broom’s final photograph of the war, showing sombre crowds assembled outside Buckingham Palace on Armistice Day in November 1918, is strikingly funereal. A complete absence of celebration suggests fatigue and personal loss.

American Expeditionary Forces arrive in London, 13 May 1918

Christina Broom: Soldiers of the American Expeditionary Forces, recently arrived in London, eat a packed lunch in a park before parading in front of King George V and Queen Mary at Buckingham Palace, London, 13 May 1918.

Buckingham Palace on Armistice Day, 11 November 1918

Christina Broom: Crowds in front of Buckingham Palace on Armistice Day, 11 November 1918.

Christina Broom never worked at the front. Her age and family circumstances ensured that she never considered it. But it would also have been fruitless for her to attempt it. In August 1914, the British military authorities made it clear that neither women nor photographers were welcome in the war zone. Given such attitudes, it is not surprising that IWM encountered numerous obstacles when it first requested permission in October 1918 for Olive Edis to visit the Western Front on its behalf. Prior to the war, Edis had established herself as a successful studio portrait photographer with studios in Norfolk, Surrey and London. For portraits, she preferred a large format 10x8 inch glass plate camera and natural lighting wherever possible. She also placed great emphasis on the importance of an artistic approach. Monochrome platinum prints and autochromes in soft colours produced formal yet flattering photographs with a strong aesthetic which verged on the painterly. Although not a suffragette, she was one of the first female professional photographers to be elected as a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society and was an active advocate of women’s photography.

Edis undertook the IWM assignment on an expenses-only basis when official permission to proceed was finally granted in March 1919. But by this time, the war had been over for four months. In many respects, Edis found herself documenting the aftermath of war on the Western Front, rather than the war itself. British wartime arrangements on the front were being dismantled and none of her subjects were at risk as a consequence of enemy action (although they were very much at risk from the notorious Spanish flu pandemic then raging throughout the world).

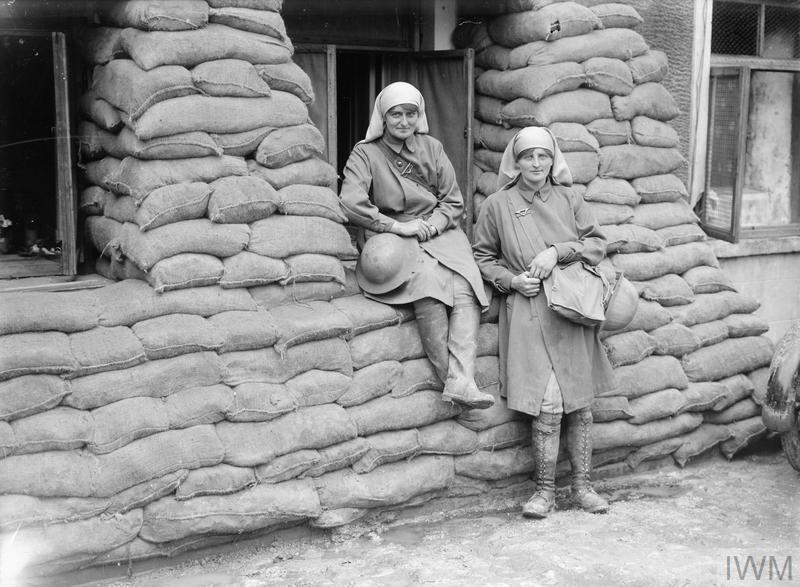

Travelling by car with representatives of IWM’s Women’s War Work Committee, Edis spent four weeks photographing British, French and American women attached to the armed forces in a variety of locations. But her studio technique and bulky camera did not transfer easily to the rigours of the Western Front. Her preference for photographing her subjects in natural light risked technical flaws, such as blurring, exposure problems and stilted poses which lacked the intimacy she sought. Nevertheless, her photographs were notably different from those of male official photographers.

Overall, Olive Edis’ photographs are an attractive body of work which offers an account of women’s wartime achievements and an affirmation of their aspirations in post war Britain. Women are shown in positions of responsibility, dominance or skill and in a broad range of roles, both novel and traditional, which exude authority without compromising their subjects’ femininity. Although men occasionally feature, they rarely appear in large numbers and almost never in positions of equality. A sense of drudgery and difficult working conditions forms a stark, if occasional, contrast to the idealised wartime images produced by male official photographers. In some cases, Edis achieves a unique intimacy by virtue of her gender. Her photograph of a hairdressing establishment for military women at Pont de l’Arche would undoubtedly have been beyond the reach of a male photographer.

RAF Pont de l’Arche, March 1919

Olive Edis: A hairdressing establishment provided for women of Queen Mary’s Auxiliary Army Corps (QMAAC) at RAF Pont de l’Arche, which enjoyed the reputation of being a regular Bond Street establishment, France, March 1919.

Despite official opposition, some British women did experience and photograph the war at close quarters in a manner which truly bridged the gender divide. Although photography was never the primary purpose for these women, their exceptional situation and experiences often influenced their photography, transforming it from a personal activity, undertaken during occasional moments of leisure, into a means of bearing witness for a wider audience. This transformation was characterised by a broadening of subject coverage, enhanced attention to the quality of the image and, on occasion, the substitution of a better quality camera.

The experience of Florence Farmborough (1887-1978) on the Eastern Front demonstrates the transforming influence of close proximity to the front line. Farmborough, who had a comfortable middle-class upbringing in Buckinghamshire, was both restless and romantic by nature. She left home, aged 21, to indulge a thirst for travel and adventure. When war broke out six years later, she was working in Moscow as an English teacher and personal companion. Farmborough’s strong affection for the Russian people motivated her to overcome language problems and train as a Red Cross nurse. In March 1915, she joined a Russian mobile medical post close to the front line on the Eastern Front. Within a few weeks, Farmborough was forced to join the Imperial Russian Army’s retreat.

Undaunted by this baptism of fire, Farnborough worked in consistently harsh conditions, treating the wounded of all nationalities until revolution and civil war forced her to flee her beloved Russia in 1918. Controls on photography were virtually unenforceable over the vast Eastern Front and Farmborough documented her experiences whenever opportunity allowed. As time went on, she was occasionally asked to photograph on a semi-official basis and upgraded her equipment accordingly. Now equipped with a medium format glass plate camera and tripod (acquired in the Crimea), she would pass exposed plates to a Russian liaison officer for processing in the rear areas. Espousing an early form of ‘citizen journalism’, Farmborough also wrote occasional eyewitness accounts which were published by The Times in Britain.

Farmborough was a gifted amateur photographer who possessed a good eye for an attractive image and was naturally observant. She possessed an instinctive sense for composition and lighting, although her style occasionally verged on the sentimental. Farmborough’s ability to set a scene to artistic effect is clearly demonstrated in a number of successful group photographs. However, her primary purpose was to document the people she encountered and the vagaries of war on the Eastern Front as she perceived them. Farmborough’s proximity to the front enabled her to access trenches and troops in the front line. She photographed the dead of both sides in graphic detail, while also documenting the pragmatism and respect which Russians soldiers accorded their dead. Overall, Farmborough’s photography demonstrates how the intense experience of war in the front line has the potential to sweep divisions of gender and class aside.

The Russian Army on the Eastern Front, 1916

Florence Farmborough: An unknown Russian dead soldier lies on the battlefield, Eastern Front, 1916.

The Red Cross on the Eastern Front, 1914-1917

Florence Farmborough: Russian nurses asleep underneath a hayrick, Eastern Front, 1915/1916.

It is undeniable that the wartime achievements of all the women featured in this article were exceptional for their time. However it is important to recognise the inspiration that they provided for the immediate post-war generation of women. Then, as now, they provided an early demonstration of what women could contribute to war photography and a visual understanding of modern conflict. Rather than allow them to fall into obscurity, we would do well to remember them.

A longer version of this article, titled A Woman's Eye: British Women and Photography during the First World War, appeared in the summer 2014 issue of Despatches, the magazine of the IWM friends.

The war photographs they didn't want you to see

Voice Over: These are the photographs they didn't want you to see.

During the Second World War, the war office couldn't risk sensitive details getting into enemy hands, so they were heavily censored.

Since the invention of Photography in the early 19th century, war photographers have risked their lives venturing into war zones in an attempt to document the reality of war with a camera.

Helen Mavin: Until the invention of Photography in the 1820s, the only way to report on war was through text and artworks such as sketches created in a hurry or paintings produced from memory. Nothing that offered the immediacy or some may argue the realism that photography could. Those who were creatively inclined, quickly realized photography's potential and the use of cameras in war zones has become increasingly important since then. There are now 11 million photographs in the Imperial War Museum's archive and the collection is growing every day.

Voice over: These images have been created by a wide range of people, from civilians caught up in conflict, to commissioned war photographers and even service men and women trying to make sense of daily life on the front line. With the development of camera phones, in recent years, photographing the realities of war is more accessible than ever but it wasn't always that easy.

Helen Mavin: The first photographed war was the American Mexican war of 1846, shortly followed by the Crimean War. Roger Fenton was one of the first to experiment with early cameras and was soon commissioned to document the developing situation in Crimea. The American Civil War became the most photographed war of the 19th century.

The earliest photographers in this period used heavy, often cumbersome or fragile equipment such as tripods and glass plate negatives. Some photographers even took their own mobile studios and dark rooms onto the battlefields.

Voice over: By the time the first world war broke out in 1914, developments and technology meant that lighter, more portable and affordable equipment such as roll film was increasingly available.

This opened up the possibility of Photography as a hobby as well as a potential career and getting close to the action had never been easier.

Helen Mavin: The first Vest Pocket Kodak Camera was now on the market. Due to its portability and affordability these cameras grew in popularity and they became known as the Solder’s Camera.

Voice over: Around 5,500 of these cameras were sold in Britain in 1914 and this rose to 28,000 sales in 1915.

Helen Mavin: This model is an Autographic vest pocket camera. It included a stylus so that photographers could make a note or description of what they had photographed.

The lens collapses down so it fits into your pocket and you could quickly take it out to operate the camera by looking down in the viewfinder in portrait or switching the viewfinder to take landscape photographs.

Voice over: It wasn't just the technology that was changing. How we viewed and used these images also started to change.

Helen Mavin: Photographs started appearing in newspapers and early picture magazines.

Voice over: The war office had also spotted the potential of photography as an instrument of war.

Helen Mavin: Throughout the first world war, the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Engineers used photography to understand the landscapes they were fighting in, producing thousands of aerial photographs and panoramic images on the ground.

Voice over: Photo reconnaissance was often the only way to collect information behind enemy lines and the results helped to inform key military decisions. But first world war photographers were about to face a new challenge to their craft.

Helen Mavin: Fearful that unpopular or sensitive photographs might make their way into newspapers and compromise the war, the war office put restrictions in place.

Voice over: Unauthorised photography was banned and on 16th of March 1915 a war office instruction

was issued which aimed to ban cameras on fighting fronts. This was subsequently followed up with further rules.

Helen Mavin: Not everyone abided by the rules, particularly away from the Western Front. Many amateur photographers risked punishment and continued to use their cameras, some even for commercial gain.

Voice over: One such photographer was Herbert Preston. While serving in the Royal field artillery, he persuaded his wife to send him his Kodak Brownie Automatic camera, which she did in a food parcel, packed between a ham and a fruit cake.

Herbert Preston was able to take many photographs of his colleagues and life on the Front. He was sending them back to his wife who sold them on to newspapers for a profit. Ernest Brooks, who had joined the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve in 1915, was the very first official war photographer appointed to the admiralty.

Helen Mavin: Ernest Brooks was sent to the Dardanelles in April 1915 to cover the Gallipoli campaign. Later in March 1916 he was also appointed the first British official photographer in France, documenting the Battle of the Somme. Brooks created many panoramas and posed pictures but he also employed a distinctive use of silhouette.

Voice over: At least nine men were employed as professional photographers by the British government during the first world war, across home and fighting fronts, but olive Edis became Britain's first commissioned female photographer in 1919.

Helen Mavin: Edis worked out of her successful studios in London and Norfolk where she had built a reputation photographing many high-profile characters.

She was approached by the women's work subcommittee of the National War Museums, later to become the Imperial War museums, inviting her to France and Belgium to photograph women in service.

Voice over: The work went ahead in March 199 shortly after the end of the first world war. Edis travelled with three cameras and dozens of glass plates and created a lasting record of women's war work, in her own recognizable style.

Helen Mavin: She preferred to use natural light rather than a flash which presented a challenge as a lot of her photos were to be taken inside. To get around this obstacle, Edis would often position her subjects near to windows, where they could be bathed in natural light.

Voice over: As a woman, Edis was able to gain a more intimate access to her female subjects

than her male counterparts. We know from her diary that she searched for the beauty in everyday scenes. Her photographs captured the private moments of women, from getting their hair done and time spent in the maternity unit, to a sensitive picture of a woman tending a grave.

Possibly for the first time, a woman's perspective of war was being seen.

After the first world war, most photographers went back to their pre-war jobs in the press or wider photographic industry. When the Second World War broke out, photographers were again relied upon, but this time it was on a much larger scale.

Helen Mavin: The British government once again recruited press photographers prior to establishing specialist units such as the Army film and photographic unit and the RAF photographic unit, to keep up with the various demands for imagery from the war, in all theatres The Ministry of Information employed high-profile photographers such as Bill Brandt and Cecil Beaton, to photograph the war on the home front and abroad.

Voice over: As with the First World War, the British government tightly controlled what could be published in newspapers and magazines through censorship of photographs.

Helen Mavin: These wartime photographs, taken by photojournalists in the UK during the second world war, were all banned for one reason or another. Photographs passed for publication were marked in blue by sensors and those stopped from being published were marked in red.

Voice over: Street names had to be obscured and clock faces scratched out. The bureau didn't want certain details revealed to enemy agents.

Helen Mavin: The latter half of the 20th century saw major shifts in the relationship between war reportage and photojournalism, fuelled in part by technological developments and the establishment of photo magazines such as Life in the 1930s, and the creation of Magnum, an agency, formed by a group of celebrated photographers all profoundly influenced by their wartime experiences.

Voice over: Propaganda and image manipulation has become a potent weapon utilised by almost every nation, continuing through conflicts such as the Cold War, the Gulf War and Kosovo. Despite this, photographic evidence of conflicts can still provide the world with unflinching insights.

Helen Mavin: To this day, the Imperial War Museums continue to commission war artists to report on conflicts and to explore its causes, course and consequences.

This photograph is from a series by photographer Paul Seawright. In 2002 he was commissioned by the Imperial War Museum's artist commissions committee to travel to Afghanistan to produce work in response to the ongoing war.

This work 'Mounds' is part of a series of works entitled 'Hidden', which picture the battle sites and minefields he encountered. The resulting photographs of minefields show a seemingly empty landscape, which in reality is both lethal and inaccessible, a consequence and legacy of the war. It has also been suggested that works in this series echo back to the 'Valley of the Shadow of Death' photographed by Roger Fenton In 1855.

Voice over: Throughout history photography has allowed those close to the action to document the visceral sensory and emotional experiences of war, from combat to medical innovation, friendship in the face of adversity, as well as war crimes and loss.

Helen Mavin: Photographs offer a visual insight into war and conflict, to those who have not personally experienced it. They have the power to document and reveal, can be used for intelligence and control and have the capacity to profoundly shape how events are seen and understood.

To the individuals that carry a camera, photography can provide a welcome distraction from the horrors of the battlefield or a means of mentally processing difficult experiences through their work.

These images bear witness to and provide evidence for the horrors of war.